Yesterday we were talking here at Fearless Parent about all the good things that go along with having kids play competitive sports. Today we’re talking about the, um, not-so-good things. Youth sports has become an arms race and it’s really hard to keep up.

Balance.

I don’t like this word. It suggests an ideal state in which the key aspects of our lives can be optimally accommodated, if only we are disciplined enough to erect and honor boundaries.

On any given day, I am not in balance. I would call my life as a wife, mom, writer, advocate, public speaker, and Executive Director of Fearless Parent and Center for Personal Rights something else—prioritized chaos, maybe. Most of the critical tasks get done as long as the kids are ok. When something is going on with the kids, however, I can get derailed. That’s what happened when my kids started playing sports.

Sports, the new parenting macho

So, right, I did say in my earlier post that baseball is a great sport my boys love.

Baseball is also a huge, time-sucking, money-sucking, energy-sucking beast.

Even if you have just one child in an organized sport, you already know just how completely it can overwhelm the family routine.

For us, rec ball had two practices and two games each week per kid. With travel ball in the mix, Nick was playing baseball six days a week. His games lasted close to two hours, and the coaches asked us to arrive early.

We raced home from school, crammed down dinner, jumped into uniform, dashed outside to warm up, gathered up the gear, and sped to the baseball field. Some days, their games were scheduled on the same day at the same time on the opposite sides of town. Other days, they had back-to-back games: We arrived at the field at 5pm and staggered home close to 10pm.

I think sports are the new parenting macho.

I have a friend with four boys, all playing baseball. She seems to hold it all together and has a ready smile every time I see her. Me? I’m doing my best to be gung ho (isn’t this all grand?) but inside…

I am whining.

- Brrrrr. Some of the games are played in seriously chilly weather. I’m shivering in a down coat rated to 20F below. Do I make the boys wear long underwear and sweatshirts?

- Chaos! The house is often a disaster, with the kitchen and laundry room vying for top honors. Meals have to be fast, and even better if the kids can eat some of them in the car. The appropriate garments have to be clean and dry (at least dry, anyway), so I am doing a gazillion loads of laundry.

- Uh-oh. There is the peril of checking email. Last minute messages bring news of field changes, time changes, forfeitures, and cancellations. It’s frowned on to be late (it shows a worrisome lack of gung ho-edness). It’s even worse to show up and realize that everyone got the e-mail except you.

Yikes, I’m complaining! [Bad mom alert] Why am I feeling guilty and oh-so-sheepish? It’s not about the disrupted family routine. I’m worried about something else.

“The Little League arms race”

For me and my husband, there’s never been any question… academics come first. Why are we, and so many other parents, making such a huge effort so our kids can play sports? Is this about our children? Or is it about us? Is anyone else asking these same questions? I’m feeling that:

- It’s time consuming. Our entire family is doing less of everything except baseball. The kids are happy though; do we take their lead? How much is too much?

- It’s expensive. The basics aren’t too bad, especially relative to other sports. Then we add in multiple teams and tournaments, extra gear, and equipment. Costs start to add up quickly. Where do we draw the line?

- It’s tempting to “keep up.” Some kids play on multiple teams at the same time. Others practice several hours at home each day in their own batting cages with an automatic pitching machine, receive private lessons from former pros, and sign up for specialized camps and clinics. Is this “the Little League arms race” described in this article? If we don’t do the same, are we selling our kids short? If we do the same, are we insane?

- Winning seems awfully important. The mood is different after a win than a loss, among adults and kids. Even when the coaches say the right things, some children get very upset when they miss a play or strike out. I know it’s just a game. So why am I holding my breath when my son is at bat?

- Some parents are intense. When the kids are playing, parents cheer. Go # 9! They offer advice. Bend your knees! Sometimes the advice is for your kid. Way too high—whaddya doin’ swinging at that? Is this a big deal? No. I don’t think Nick cares. Does it hurt my feelings? Yes.

It feels that baseball has become a way parents prove to the world that our kids—and we, by association— are impressive.

Is the pressure good for kids?

If I’m honest with myself, the above gripes are pretty straightforward parenting concerns, to assess and resolve. They’re in the job description. What I really agonize over is the pressure on our kids to perform.

It’s the bottom of the last inning of a really important game (aren’t they all?). Your team is down by one, bases are loaded, there are two outs, you’re at bat, and it’s a full count… three balls, two strikes. Everyone is on their feet. Your teammates are cheering you on.

There are two outcomes, and one of them really stinks. Failure isn’t just a personal loss; it’s a team loss, too. No one is thinking about the errors in the first five innings. It all comes down to your kid. Nick is now 9. I sure hope he’s not feeling what I’m feeling. I want to throw up.

On my son’s rec team, all the kids played and rotated through a variety of positions. They placed first in the league, and Nick was the lead pitcher. To protect pitchers from injury officials limit the number of pitches thrown, so it isn’t possible to pitch for rec and travel. This worked out well. Both teams had lots of good players, and Nick couldn’t have been happier.

Then he had what people sometimes call a growth experience.

It was a tournament game for his travel team, and the lead pitchers were bumping up against pitch count limits. To everyone’s surprise, the coach put our son in. This was his pitching debut on travel, and he… bombed.

Spectacularly.

Nick threw bad pitch after bad pitch, staying in for what seemed an eternity—his full pitch count. He was rattled. His shoulder hurt. He was not having fun.

To his credit, he hung in there and kept it together.

To his utter mortification, the officials terminated the game early, under the mercy rule when the other team leads by 10 runs. Losing is bad. To be “mercied” is completely humiliating.

I was out of town, so I only heard about it. When Nick called me on the phone after the game, I wished more than anything that I could’ve been there to comfort him.

My husband, who is not prone to hyperbole, said it was painful to watch. He felt that Nick lost the game. We reminded each other about the great life lessons that kids learn from sports.

It’s character building.

It’s useful to learn how to perform under pressure.

It happens.

This is what it means to play competitive sports.

Yes, those things are certainly true. We were also trying to console ourselves. That day, that game, just sucked.

Or is this really about me?

When I think about Nick’s pitching episode, I wince. (There, I just winced again.) I even feel a little self-conscious when I’m around the other parents. I want to tell them that Nick had shoulder pain, and he didn’t tell anyone. Sometimes, I do worse. I catastrophize. I play a bad game in my head. It’s called “What if?”

What if it happens again?

What if he doesn’t get another chance?

What if he doesn’t make the travel team next year?

My son has moved on but I haven’t. He was devastated for one day, and the moment passed. Nick can talk about it calmly. He still loves baseball. He still wants to pitch. I know this earns me a Bad Mom Award, but I’m perseverating over the humiliation of that game. Don’t judge me too harshly. I’m judging myself too, and wondering what my attachment to (ok, obsession with) my son’s performance says about me.

When a response is disproportionate to the event, it means there’s something else going on. I get it.

Here’s what I now understand. My boys were sick when they were little. Doctors painted a grim prognosis. They basically told us their ailments were incurable and my children would never lead normal lives. I rejected their pat conclusions, but I was very, very scared.

If you have a child with a medical condition or a child on the autism spectrum, I know you understand what I mean. I was on my knees. I bargained with God. I believed they’d get better, but I was afraid to hope for too much.

This was a long time ago. They’re better now and they’ve been better for a long time. But the fear never entirely goes away. I don’t think it ever will.

When my boys are doing well in sports, it means the ten doctors who confidently told me my children’s ailments were lifelong and we should prepare accordingly were impressively, fabulously, extravagantly…

Wrong.

Incorrect.

Mistaken.

Wide of the mark.

Boy-oh-boy does it feel great to write those words.

When my boys are doing well in sports, it is a final affirmation that they aren’t sick anymore.

Yikes! That’s a lot to put on a kid. That’s a lot to put on a game. I am grateful it only took me a year to figure it out. It’s not baseball that’s bad. (Because, as you know, I love baseball.) It’s when baseball becomes a place where parents inadvertently act out their own issues. Knowing this helps me to keep perspective and enjoy my son’s games.

I wish I was done, but I’m not. There’s more. It’s not always comforting to be in good company. In tomorrow’s final installment, I share what some experts are saying about youth sports. They’re raising important concerns and putting them on the radar for all adults—parents and guardians, coaches, instructors, and athletes—who care about the children.

Second in a series of three articles (Part 1). Rounding the bases: Youth Sports and Bad Behavior (Part 3). This series also appeared in Pathways Magazine

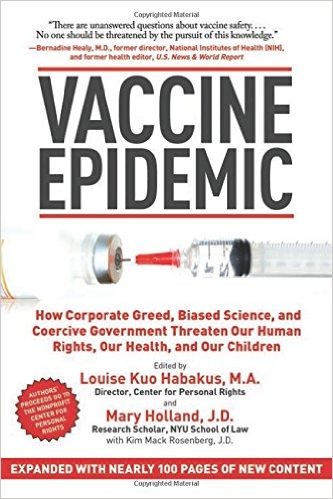

Louise Kuo Habakus is Executive Director of Fearless Parent and was last seen checking out prices of used batting cages on ebay.

Louise Kuo Habakus is Executive Director of Fearless Parent and was last seen checking out prices of used batting cages on ebay.

Fun read! Very entertaining, articulate, insightful, and soul searching on experiences for parents whose children play baseball and beyond. We can all relate to it!

Of all of life’s lessons learned from sports, it sounds like the one Nick has learned best is “keep your eye on the ball.” Kudos to him for putting the defeat behind him and not letting it change the way he feels about the sport he loves. Maybe the fact that he’s overcome so much helps him keep setbacks like this in perspective.

Thoroughly enjoyed reading your two posts on baseball (good and bad), entertaining and soul searching. As a Chinese from Mainland China, I had no exposure to baseball until my son first touched his baseball glove and bat and instantly fell in love with baseball when he was 7, the spring of his 2nd grade. Our life has been changed ever since. I experienced every bit of what you have experienced and more since my son now is the youngest member of the high school freshman team and is going into sophomore this fall. He is the only Asian in the team. There have been so much my son and we as parents went through in the past 7 years that I can write a book about it. We are forever more uncertain at this point on what baseball’s place in his college pursuit and beyond but I will just say that his passion for baseball is still burning and we will be there to support him and cheer on for him. Over the years one thing that worked for us is that we, including my son learned not to idolize baseball (or for that matter any other youth sports or activities). Baseball has taught him many valuable lessons and the best gift he got from baseball is the commitment, the resilience to failures and very good time management. My son is hard working and humble, and so far has managed the most rigorous level of academics at school while playing baseball 6 days a week spring and summer and some more in fall. Only time will tell how my son will do with his life but somehow I want to believe that baseball has prepared him well in some aspects. Jackelyn